Eat With the Sun: Aligning Meal Timings with Your Body Clock (The Circadian Rhythm Approach)

We often hear “what” to eat for health, but rarely “when.” Yet timing your meals may matter as much as your macros. In fact, ancient Indian traditions and modern chronobiology agree on one surprising truth: when you eat can shape how well you digest, absorb, and metabolize your food.

Welcome to the science (and simplicity) of eating with the sun—syncing your meals with your body’s natural circadian rhythm.

What Is the Circadian Rhythm?

Your circadian rhythm is your body’s internal 24-hour clock. It controls everything from your sleep-wake cycle to hormone release and even how your body processes food.

Your digestive system isn’t “on” 24/7—it works in cycles. Aligning your meals with your circadian rhythm can lead to:

-

Better digestion

-

Balanced blood sugar

-

Improved energy

-

Deeper sleep

-

Reduced cravings and weight regulation

Ayurveda has long supported this idea, encouraging eating in tune with Agni (digestive fire), which is said to be strongest at midday and weakest after sunset.

Why Eating With the Sun Works

-

Morning (6 am – 10 am): Body is waking up, cortisol is high, digestion is starting to ramp up. Light, warm meals support this natural flow.

-

Midday (10 am – 2 pm): Peak metabolic activity. This is when digestive enzymes and bile are at their best—perfect time for your main, heaviest meal.

-

Evening (after 6 pm): Digestive function slows, melatonin starts rising. Heavy meals at this time are harder to break down, often disturbing sleep and weight balance.

How to Align Your Meals with Your Circadian Clock

Here’s a practical breakdown of meal timing and composition:

1. Morning (6:00 – 9:00 AM): Ease Into the Day

Why it matters: Your body is just waking up, and digestion is still gentle.

Eat:

-

Warm, light foods like soaked nuts, fruits, ghee-roasted poha or upma

-

Herbal teas, warm water with lemon or cumin

-

Small portions of protein and complex carbs

Avoid:

-

Cold smoothies, heavy dairy, fried foods

-

High caffeine right after waking (wait 60–90 mins)

2. Mid-Morning (9:30 – 11:30 AM): Optional Mini-Meal

Why it matters: This is when your body is moving into its metabolic groove.

Eat (if hungry):

-

A fruit, handful of seeds/nuts, buttermilk

-

Light smoothies (not ice-cold), or a small bowl of curd with spices

Tip: Stay hydrated with jeera-ajwain or fennel water for digestion.

3. Lunch (12:00 – 2:00 PM): The Main Event

Why it matters: This is when your digestive fire (Agni) is at its peak. Your body can handle the most complex meal now.

Eat:

-

Balanced thali: dal, sabzi, whole grain (roti, rice, millet), curd, ghee

-

Include cooked vegetables and a small salad (not cold)

-

A small sweet post-lunch is acceptable here (like jaggery-based treats)

Avoid:

-

Skipping lunch or eating on the go

-

Heavy desserts or packaged drinks

4. Evening Snack (4:00 – 6:00 PM): Refuel Without Overloading

Why it matters: Cortisol dips, blood sugar may fall—smart snacking prevents bingeing later.

Eat:

-

Roasted chana, makhana, vegetable soup, fruit with nut butter

-

Herbal teas like tulsi or ginger

Avoid:

-

Sugary snacks, caffeine-heavy drinks

-

Fried snacks or cold beverages

5. Dinner (6:30 – 8:00 PM): Keep It Light and Early

Why it matters: Your digestive system is winding down. Eating too late or heavy can impair sleep and metabolism.

Eat:

-

Soups with moong dal, soft khichdi, lightly sautéed veggies

-

Small portion of grains with a protein (egg, tofu, paneer, dal)

-

Herbal teas like chamomile or cumin water post-meal

Avoid:

-

Raw salads, heavy desserts, late-night snacks

-

High-fat, high-protein meals at night

6. Fasting Window (Post 8 PM – 8 AM): Time for Repair

Why it matters: Giving your digestive system 12 hours to rest supports gut repair, insulin sensitivity, and detox pathways.

Tip: Try not to snack after dinner. Let your body focus on healing—not digesting.

Ancient Wisdom Meets Modern Science

-

Ayurveda: Encourages eating largest meal at noon and light dinners

-

Chrono-nutrition studies: Show better blood sugar, weight, and lipid profiles in people who eat earlier in the day

-

Modern advice: Intermittent fasting (especially early time-restricted eating) overlaps with this approach

Simple Weekly Meal Timing Plan

| Time of Day | What to Eat | Why It Works |

|---|---|---|

| 7:30 AM | Warm water + soaked nuts | Kickstart metabolism gently |

| 9:00 AM | Light breakfast (poha, fruit, sprouts) | Supports gentle digestion |

| 1:00 PM | Heaviest meal (full thali) | Max digestive capacity |

| 5:00 PM | Snack (nuts, soup, fruit) | Prevents overeating at dinner |

| 7:30 PM | Light dinner (khichdi, soup) | Prepares body for rest |

| 8:30 PM onwards | Digestive teas, fasting window | Supports gut healing |

Conclusion: Timing is Nourishment

What you eat is vital—but when you eat is equally powerful.

Eating with the sun is not about being rigid; it’s about listening to your body’s rhythms and honoring them.

Whether

you’re looking to improve digestion, balance hormones, or support

overall wellness—meal timing might be your missing link.

Start small. Shift one meal. Watch the difference.

Key takeaways:

~ There are five key elements to weight loss from a circadian point of

view: Timing of Meals; Light Exposure; Sleep; What to Eat and When; and

Genetic Variants.

~ All of these can come together in our modern world to give you the

propensity to gain weight – and all can be hacked to help you lose

weight.

How does circadian rhythm impact weight loss?

#1: Timing of Meals

Timing is everything when it comes to our bodies.

Midnight snacks, a bowl of cereal before bed, or even ‘saving’ dessert until 9 or 10 pm. All of these are fairly normal behaviors these days. Just open up the fridge and pop something in the microwave to heat it up anytime, day or night. Modern convenience at its best; not something our ancestors would have been able to do.

This penchant for eating at any time, day or night, drives the obesity epidemic.

It is always interesting to look at animal models and agriculture to understand weight gain. Financially it makes the most sense to have animals gain weight quickly for food production, so a lot of research has gone into this topic. For example, farmers have known for decades that low doses of antibiotics increase the weight of cattle. When it comes to the timing of eating, it has been known for a long time also that the amount of weight gained for the same quantity of food depends on the time of day that the food is given. For example, a study from 1982 found that catfish gain more weight when fed at a specific time of night.[ref] A more recent example is a mouse study from 2009 that found that mice fed during the time that they normally would be resting gained more fat although they ate the same number of calories as mice fed during their active period.[ref][ref]

Let’s take a look at the research on people:

A study of a Mediterranean population of 420 looked at weight loss over a

20-week diet. Those who ate earlier in the day (defined here as eating

lunch before 3 pm) lost more weight than those who ate later in the

day.[ref]

Another study found that “Eating late is associated with decreased resting-energy expenditure, decreased fasting carbohydrate oxidation, decreased glucose tolerance, blunted daily profile in free cortisol concentrations and decreased thermal effect of food..”[ref]

One more example from a 2017 clinical trial that looked at the timing of meals in healthy 18-22-year-olds: “These results provide evidence that the consumption of food during the circadian evening and/or night, independent of more traditional risk factors such as amount or content of food intake and activity level, plays an important role in body composition.”[ref]

Finally, let’s sum this up with the first sentence from a study on circadian misalignment and glucose tolerance. “Glucose tolerance is lower in the evening and at night than in the morning.” Yes, the study goes on to quantify this as being 17% lower glucose tolerance at 8 pm vs. 8 am.[ref]

Lifehacks:

The simple solution is to eat earlier in the day and not snack at night. For some of us, this is easier said than done. So make a plan for your meals for a few days. Yes, actually, sit down with a pencil and paper and come up with ideas for shifting your calories to the morning hours. If you are a habitual TV watcher at night (with a subsequent bowl of popcorn and a beer), plan out a couple of evening activities to get you out of the house for a few evenings while you break the snacking habit. Perhaps go for a walk, watch a movie, avoid the overpriced snacks, or dust off your bowling shoes for a quick game.

While this may sound a bit cut-and-dried, we are flexible creatures, able to withstand periodically eating at different times without drastic effects. The bigger picture is the chronic effects of eating at the wrong time, rather than just the one-off change up of our daily eating habits. So don’t beat yourself up if you nibble on something at an evening event. Just get back on track for the rest of the week.

#2: Light Exposure

Light is also important to weight gain. While it seems strange to think about it, the research on this topic points to an incontrovertible conclusion that light – both bright light exposure in the daytime and no light exposure at night – makes a significant difference to our weight.

Science-y Stuff about light and the Circadian Clock:

In Circadian Rhythm Connections, Part 1: Mood Disorders, I explained how light at a specific wavelength (~480nm, blue light) hits melanopsin-containing photoreceptors in our eyes, signaling to our core circadian genes (CLOCK, BMAL1) in the brain that it is daytime.

Our body has both the strong central circadian clock in the brain’s suprachiasmatic nucleus and peripheral clocks in our organs. These peripheral clocks include the timing of functions in the liver, pancreas, etc.

The core clock genes are mainly entrained through the cycle of light and darkness, while the peripheral clock in the liver is reset quicker or entrained by food intake. But the core clock genes do still affect the peripheral clocks.

The core circadian clock’s location resides in a hypothalamus region called the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN). The SCN signals to the adrenal system to increase adrenal glucocorticoids (e.g., cortisol is a glucocorticoid hormone) production just prior to waking. “This promotes arousal and alertness by enhancing liver gluconeogenesis (from amino acids and fatty acids), promoting the release of liver glucose to the blood, and increasing its uptake in the brain and muscles. Adrenal glucocorticoids have been implicated as a peripheral humoral cue for the entrainment of oscillators such as the liver.”[ref] The SCN also controls the circadian rhythm of the hormones insulin, glucagon, and adrenalin.

That may sound like science mumbo-jumbo, but it has practical implications. For people waking up at 3:30 or 4:00 am every night, this could be caused by the circadian spike in cortisol levels. Personally, I used to see 4:00 am on the clock quite often. Blocking blue light in the evenings, going to be at a reasonable hour, and cutting out snacking after dinner has eliminated the 4 am wake-up for me.

Weight gain and light at night:

Moreover, animal studies for efficiently producing more meat show us a lot. Chickens have been studied under different lighting conditions for many decades to determine the quickest way to have plump chickens. One study found that chickens exposed to specific wavelengths of light (450-630nm) pack on the pounds better when exposed to the light from 8 am until midnight. The study also notes that poultry workers are adversely affected by blue or green wavelengths of light at night and thus suggests using light in the yellow wavelengths is almost as effective for chicken fattening.[ref]

What does light at night do to people? Shift work seems to be a risk factor for obesity. One study of rotating shift workers (Canadian men) found a 57% increase in the risk of obesity.[ref] Another study of shift workers (Korean women) found a 63% increased risk of obesity.[ref] Numerous other studies have similar results.

You may think that all those shift workers are eating bags of Doritos all night. Perhaps. But even a dim light at night has been linked to weight gain in animal studies that control for the number of calories eaten.[ref] Another mouse study looked at the effects of dim light at night (5 to 15 lux – similar to a night light) and found that mice fed the same number of calories gained weight when exposed to either dim or bright light at night.[ref]

Dim light at night seems to affect human weight as well. A large study looked at the amount of light in a bedroom at night and correlated higher light amounts to higher BMIs.[ref] Other studies have repeatedly shown the same results.[ref]

Lifehacks:

Solving this problem is as simple as shutting off that night light, getting some blackout curtains, and eliminating all the glowing LEDs from chargers in your bedroom.

Not enough light during the daytime:

Our modern world of cubicles and working indoors also affect our waistlines. Studies show a link between more light during the day — specifically outdoor light during the morning hours — and weight loss.[ref] One study that tracked people’s light exposure concluded “having a majority of the average daily light exposure above 500 lux (MLiT500) earlier in the day was associated with a lower BMI.”[ref] A study of people in the northern latitudes during the winter found that bright light therapy in the morning increased weight loss and suppressed appetite.[ref]

Lifehacks:

With this in mind, make getting outside during the morning a priority. Drink your coffee on the porch, walk or bike to work, take a morning break outside, and eat lunch outside if possible.

#3: Sleep

Sleep is something that every health guru out there puts on their lists of “Top 5 ways to improve blah, blah, blah.” But does it really affect our weight and metabolism that much? Is the benefit worth the trade-off – e.g., is it worth going to bed before 11:00 each night rather than staying up late, having fun with friends, or working long hours? Quick answer: Yep. Research shows that it really does make a significant difference.

Fun facts: The average amount of sleep per night has decreased by about 1.5 hours over the last century.[ref] And the recommended amount of sleep for children has decreased by over an hour from 1897 to today.[ref]

Not-so-fun fact: A meta-study of 75,000+ people found that sleeping 5 hours per night or less increased the risk of having metabolic syndrome (e.g., high blood pressure, high blood sugar, overweight) by over 50%. To avoid an increased risk of metabolic syndrome, participants had to sleep over seven hours a night.[ref]

A 15-day in-patient study examined the effect of 5 days of insufficient sleep, mimicking the effects of not sleeping enough during the workweek. The study found insufficient sleep caused greater energy expenditure, but that extra energy expenditure was offset by greater food intake. After the two-week trial, participants had gained almost 2 lbs. Women were more likely to be affected by weight gain than men. (Impact of insufficient sleep on total daily energy expenditure, food intake, and weight gain) Another larger study had similar findings, with additional results showing that African Americans gained slightly more weight than Caucasians with sleep insufficiency.[ref]

Another study looked at sleep insufficiency (5 hours/night of sleep) and found that insulin sensitivity decreased and inflammatory markers increased.[ref]

Sleep timing also matters. A study looked at the average sleeping time (over a week-long period) and BMI. The results showed that those who were late sleepers (the midpoint of sleep after 5:30 am) had an average higher BMI and a greater percentage of calories eaten after 8 pm.[ref]

So that was just three studies; hundreds of more studies on this topic show similar results. The science is clear and unambiguous on this topic.

Why sleep is important to our metabolism:

There are several players involved here, with melatonin being an important one. Melatonin, a hormone that rises and peaks at night while we sleep, is important to our basal metabolism for a couple of reasons that I will go into below. Light at ~480nm (blue wavelength of light) hitting the retina of our eye stops melatonin production. It is surprisingly quick, with 15 seconds of light stopping melatonin production for over 30 minutes and two minutes of blue light suppressing melatonin for more than 45 minutes.[ref] Thus, turning on the bathroom light in the middle of the night means it will take a long time to fall back asleep.

Thyroid and basal metabolic rate:

What is melatonin doing at night while we sleep? Among other things (like acting as an antioxidant), melatonin modulates the secretion of leptin, the hunger hormone. Melatonin receptors also regulate the synthesis and secretion of thyroid hormones. “During long photoperiods, higher levels of TSHβ and DIO2 favors the conversion of thyroxine (T4) to triiodothyronine (T3), increasing energy expenditure and basal metabolic rate. Lower, short-photoperiod levels of TSHβ promote dominant DIO3 activity, which converts T4 to both inactive reverse T3 and diiodothyronine T2, increasing food intake and adipose deposits.”[ref]

Glucose metabolism and insulin resistance:

First, let’s take a look at a 2003 study that just kind of makes logical sense. The study looked at medical students who were ‘nocturnal’ – e.g., staying up until 1:30 am and sleeping in until 8:30 am – vs. those who were ‘diurnal’, which would be going to bed well before midnight and getting up when it is light. The nocturnal med students skipped breakfast and ate more of their calories later at night. This caused glucose impairment as well as decreased melatonin and leptin secretion.

It has been known for decades that people are more insulin sensitive in the morning (again, why we shouldn’t eat a big meal at night).[ref] Another study states: “Multiple studies have shown that in healthy humans, both insulin sensitivity and beta-cell responsivity to glucose are lower at dinner than at breakfast”. It goes on to explain that mouse models show that deleting one of the core clock genes (BMAL1) in the pancreas causes insulin resistance.[Multiple studies have shown that in healthy humans, both insulin sensitivity and beta-cell responsivity to glucose are lower at dinner than at breakfast] Circadian disruption is intimately coupled with poor glucose metabolism and insulin resistance.

Lifehacks:

Blue

light at night effectively shuts down melatonin production, so you need

to block all blue wavelengths for a couple of hours before bed. You may

be thinking… “ha! I don’t need to wear silly-looking blue-blocking

glasses because I have night shift enabled on my phone/tablet.” Well, it

turns out that researchers studied the night shift mode

in a couple of different settings, and it did very little to prevent

melatonin production from being suppressed. So either put away

electronic devices a couple of hours before bed or get a pair of

blue-blocking glasses.

It takes a couple of weeks to get your body’s melatonin production up to optimal after you start blocking blue light at night. In the meantime, you could increase your consumption of foods that contain melatonin. Foods high in melatonin include tart cherries, grapes, and almonds. Interestingly, melatonin levels also fluctuate in plants, so the time of harvest, season, and other environmental conditions may affect the levels found in plants.

Why not take a melatonin pill instead of blocking blue light at night? Well, your body’s melatonin production (without unnatural light) is a bell-shaped curve. Taking a pill immediately gives you a big dose that gets metabolized and eliminated. Most people are better off increasing their natural production of melatonin.

#4: What and when to eat

The liver coordinates our metabolism through the synthesis of lipids from carbohydrates and the storage of both fats and carbs as glycogen. The liver’s peripheral circadian clock is powered by both the SCN (core clock) and feeding timing. Also, the CLOCK and BMAL1 genes participate in the rhythm of glucose metabolism and release.

What does this mean? Our body breaks things down (metabolize) better at different times of the day. This applies to everything coming into the liver – from foods we eat to toxins we are exposed to. Here are a couple of studies on food as examples:

A study of 93 overweight women examined the effects of a higher-calorie breakfast or a higher-calorie dinner over a 12-week diet plan. The results showed that those eating the higher calories at breakfast lost 2.5 times as much weight as the high dinner group. The higher-calorie breakfast group also had a decrease in triglycerides by 33% compared with the high-calorie dinner group, which had an increase in triglycerides.

A mouse study found that mice given glucose during their rest period gained more weight than those given the same amount during their active period.[ref]

Generally, we can sum it up as glucose metabolism is best in the morning.[ref] It makes sense if you are eating a mixed diet of carbs, proteins, and fats to shift your carb intake towards the morning hours and eat fewer carbs at your evening meal. This is even more evident in studies of people with impaired glucose tolerance. One study examined the differences between high fat in the morning and high carb in the evening or the reverse (high-carb morning/high-fat dinner). It found that the high-fat morning/high-carb dinner “shows an unfavorable effect on glycaemic control,” especially in those with already impaired glucose tolerance. “Consequently, large, carbohydrate-rich dinners should be avoided, primarily by subjects with impaired glucose metabolism.”[ref]

What about time-restricted eating?

Time-restricted eating (TRE) is a concept whereby people eat all of their daily calories within a specific window of time. Several good animal studies have shown that eating the same number of calories during a restricted feeding window (8 hrs to 10 hrs) causes mice to weigh less than the control groups that are eating the same number of calories spread throughout the 24-hour day. It can also reverse the progression of metabolic diseases such as type-2 diabetes.[ref][ref]

What time of the day should you do TRE?

A time-restricted feeding study for an 8-week period had participants

eating their normal amount of calories during a 4-hour window in the

evening (5 – 9 pm). Participants did lose a little weight, but they also

had increased fasting blood glucose levels and impaired glucose

tolerance.[ref]

This indicates that a time-restricted feeding plan at any time reduces

weight, but the feeding window needs to be earlier in the day to not

impair glucose tolerance.

TRE doesn’t have to be nearly as strict as a four-hour eating window to be effective. A study of overweight individuals who normally had a 14-hour eating window found that reducing their eating window to 10-11 hours caused them to lose about 7 lbs over 16 weeks. This was maintained over the next 12 months.[ref]

A cross-over study had participants eat their first meal of the day either a half-hour or 5.5 hours after waking. One of the findings suggested PER2 (core circadian rhythm gene) expression was delayed by about an hour when the people shifted their mealtime later in the day. Another finding was that glucose levels remained high in those eating late.[ref]

Lifehacks:

The research really is good on the effectiveness of a time-restricted eating program. If you are the type of person who likes experimenting and who needs to set some rules for yourself, try a TRE program. For example: eat a good breakfast at 7:30 before heading out the door to work, lunch around noon, and then finish up with a light meal around 6:30 pm. This gives you an 11-hour eating window. Simple. And effective.

#5: Genetics

Of course, I have to talk about genetics here. We are all different, and our genes affect our natural circadian rhythm. I’ve also written other articles on this topic, so I won’t go too in-depth here.

The most obvious example of genes affecting our circadian rhythm and propensity to gain weight is the CLOCK (Circadian Locomotor Output Cycles Kaput) gene. This is one of our core circadian genes, setting the daily rhythms for the rest of our body.

One well-studied variant of the CLOCK gene is known as 3111T/C or rs1801260. Those who carry the T/T (A/A for 23andMe orientation) genotype have the normal type, while those who carry a C (G for 23andMe orientation) allele (C/C or C/T) are thought to have higher expression of the CLOCK gene and of PER2. Those with C/C or C/T are more likely to be obese, and in a clinical trial, they lost 23% less weight than those with T/T on the same type of diet.[ref]

Members: Log in to see your data below.

Not a member? Join here.

Membership lets you see your data right in each article and also gives

you access to the member’s only information in the Lifehacks sections.

Check your genetic data for rs1801260 (23andMe v4, v5, AncestryDNA):

- G/G: higher activity in the evening, possible delayed sleep onset, the risk for obesity

- A/G: somewhere in between

- A/A: typical

Members: Your genotype for rs1801260 is —.

A small trial with 40 middle-aged women (half were T/T, half were C/T or C/C) found those carrying the C allele lost less weight (about 7 lbs less) and also woke up ~30 minutes later in the morning. They also ate breakfast about an hour later than those with T/T. Additionally, the study looked at heart rate variability and several markers of autonomic nervous system function. It found that “As compared with T/T carriers, risk allele C carriers had a reduction of 34–57% in the daily rhythm amplitude of parasympathetic activity…” The C allele carriers had reduced parasympathetic tone during the night and increased parasympathetic tone during the day. Think of it as an overall flattened sine wave. The study also found that those with higher amplitude (think taller sine wave graph) of parasympathetic tone had greater weight loss during the 30-week study.[ref]

Overall, the CLOCK gene variant leads to an ‘evening’ chronotype. Bipolar patients carrying the C allele are, on average, likely to stay up 79 minutes later at night and sleepless on average as well.[ref] Bariatric surgery patients who carry the variant are more likely to be evening types and also to lose less weight than those without the variant.[ref]

Another study of this variant showed that morning gastric motility may be slower in C allele carriers. Variant carriers also had somewhat lower morning diastolic blood pressure.[ref] This may play a role in timing for breakfast, with C allele carriers perhaps wanting to eat breakfast an hour or two later.

Lifehacks:

Around 30 – 40 percent of the population carries this CLOCK gene variant. It may be even more important for these people to watch their blue-light exposure at night so that they aren’t fighting a lack of melatonin alongside their natural propensity for staying up a little later. Get into a good routine for getting to bed at a reasonable hour, and, if possible, shift your morning work schedule a little later to allow you to get enough sleep. Yes, I know that is easier said than done. While you may not be the person who wants to get up at 6:30 am, this variant is more of an hour or two shift rather than an ‘I should sleep in until noon’ excuse.

Related Articles and Topics:

Circadian Rhythms: Genes at the Core of Our Internal Clocks

Circadian rhythms are the natural biological rhythms that shape our

biology. Most people know about the master clock in our brain that keeps

us on a wake-sleep cycle over 24 hours. This is driven by our master

‘clock’ genes.

Is intermittent fasting right for you?

Intermittent fasting and ketosis have a lot of benefits, but they may

not be right for you. Your genes play a role in how you feel when

fasting.

Color TV has made us fat: melatonin, genetics, and light at night

Melatonin is vital to good health — impacting weight, cancer,

Alzheimer’s, and more. Learn how your genes interact with melatonin.

Circadian Rhythm and Your Immune Response to Viruses

Your circadian rhythm influences your immune response. Learn how this

rhythm controls white blood cell production and why melatonin protects

against viral and bacterial infections.

About the Author:

Debbie Moon is a biologist, engineer, author, and the founder of Genetic Lifehacks

where she has helped thousands of members understand how to apply

genetics to their diet, lifestyle, and health decisions. With more than

10 years of experience translating complex genetic research into

practical health strategies, Debbie holds a BS in engineering from

Colorado School of Mines and an MSc in biological sciences from Clemson

University. She combines an engineering mindset with a biological

systems approach to explain how genetic differences impact your optimal

health.

Abstract

Circadian rhythms are 24-h cycles regulated by endogeneous molecular oscillators called the circadian clock.

The effects of diet on circadian rhythmicity clearly involves a relationship between factors such as meal timings and nutrients, known as chrononutrition.

Chrononutrition is influenced by an individual’s “chronotype”, whereby “evening chronotypes” or also termed “later chronotype” who are biologically driven to consume foods later in the day.

Research in this area has suggested that time of day is indicative of having an influence on the postprandial glucose response to a meal, therefore having a major effect on type 2 diabetes.

Cross-sectional and experimental studies have shown the benefits of consuming meals early in the day than in the evening on postprandial glycaemia. Modifying the macronutrient composition of night meals, by increasing protein and fat content, has shown to be a simple strategy to improve postprandial glycaemia.

Low glycaemic index (GI) foods eaten in the morning improves glycaemic response to a greater effect than when consumed at night.

Timing of fat and protein (including amino acids) co-ingested with carbohydrate foods, such as bread and rice, can reduce glycaemic response.

The order of food presentation also has considerable potential in reducing postprandial blood glucose (consuming vegetables first, followed by meat and then lastly rice).

These practical recommendations could be considered as strategies to improve glycaemic control, rather than focusing on the nutritional value of a meal alone, to optimize dietary patterns of diabetics.

It is necessary to further elucidate this fascinating area of research to understand the circadian system and its implications on nutrition that may ultimately reduce the burden of type 2 diabetes.

Diabetes mellitus remains a leading chronic disease in the world with the number of diabetics quadrupling in the past three decades1.

The International Diabetes Federation (IDF) estimated that 415 million adults had diabetes in 2015, and by 2040, it is projected to reach 642 million2. In concert pharmacological interventions, dietary interventions remain the cornerstone of diabetes prevention and management. The key therapeutic approach to reducing the incidence and severity of type 2 diabetes focuses on the nature and quality of nutrients consumed.

Circadian rhythms are 24-h cycles regulated by endogeneous molecular oscillators called the circadian clock3.

The mammalian circadian system comprises of various individual tissue-specific clocks. This circadian clock prepares the body for events that take place throughout the day.

These include physiological parameters such as hormone secretion, heartbeat, renal blood flow, the sleep-wake cycle and body temperature fluctuations4. The circadian clock is located in the suprachiasmatic nuclei (SCN) and is a central regulator of the peripheral clock system. It plays an important role in regulating several physiological processes which synchronizes to the central 24-h circadian rhythm5.

When the SCN is destroyed, circadian rhythms of the sleep cycle and the release of various hormones diminishes. The SCN contains several types of peptide-synthesizing neurons that are essential for the entrainment and shift of circadian rhythms with the most prominent being the somatostatine neurons, vasoactive intestinal peptide and arginine vasopressin6. Ensuring circadian rhythmicity is crucial in influencing and regulating metabolic processes by regulating the expression and/or activity of enzymes involved in glucose metabolism. In recent years, a growing body of evidence is emerging that the circadian clock system can interact with nutrients to influence bodily functions. This relatively new field is described as “chrononutrition”7,8. In modern society, numerous occupations and the high prevalence of insomnia lead to lifestyles that are not aligned with their circadian clock9. The lack of alignment with the circadian clock has been reported to influence food intake, glucose metabolism, weight regulation and obesity10,11,12.

Although animal and cell models have been the experimental focus in delineating the impact of the circadian clock on physiological and nutrition, an emerging body of evidence is also being generated from human studies. The present review (although focusing predominantly on healthy subjects) aims to collate information that is also relevant to diabetics in relation to their meal timings and nutrient intake influencing glycaemic control.

Circadian rhythm

Circadian rhythm and glucose metabolism

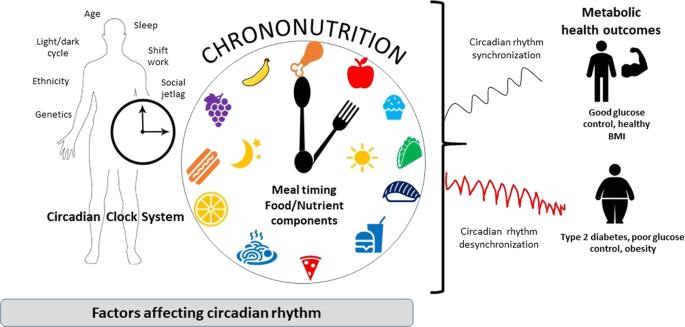

From a chronobiological point, glucose metabolism in humans follow a circadian rhythm through diurnal variation of glucose tolerance that typically peaks during day-light hours, when food consumption usually happens and reduces when it comes to night-dark hours when fasting usually occurs13. Several hormones involved in glucose metabolism, such as insulin and cortisol, exhibit circadian oscillation14,15. For example, experiments in rodents have shown the importance of the circadian system in glucose metabolism with changes in insulin sensitivity and insulin secretion patterns inducing highly rhythmic changes, thus affecting blood glucose levels16,17,18. Therefore, insulin secretion and sensitivity are closely regulated by circadian control and have strong effects on glucose metabolism. Unusual meal timings can cause glucose intolerance by affecting the phase relationship between the central circadian pacemaker and peripheral oscillators in cells of the liver and pancreas in rodents19. Similarly in humans, timed meal intake is also driven by the SCN, play a role in synchronization of circadian rhythms in peripheral tissues, thereby affecting glucose metabolism7,8,20. The effects of diet on circadian rhythmicity clearly involves a relationship between factors such as meal timings and nutrients (chrononutrition), that can contribute to circadian perturbance and influence the manifestation of metabolic disorders such as type 2 diabetes (Fig. 1).

Meal timing and dietary components (chrononutrition) play an important role in regulating circadian clocks, to enhance metabolic health and reduce the risk of type 2 diabetes.

Meal timings and glucose metabolism

Skipping breakfast and late meal time

Since the middle of the 20th century, eating patterns have shifted towards later eating times with over one-third of the caloric intake consumed after 6 pm21.

This late-eating pattern, common in the modern lifestyle today, may lead to circadian misalignment and therefore exert a negative impact on glucose control.

Circadian misalignment is also increasingly found in night shift workers. As human beings are diurnal species and generally sleep at night, shift workers are prone to developing sleep disturbances when the relationship between the light-dark phase and food intake is desynchronized.

Considerable epidemiological evidences have shown that the disruption of the biological circadian clock is negatively associated with various metabolic diseases such as obesity, cardiovascular disease, gastrointestinal problems and diabetes4,22. Shift workers tend to have a higher basal metabolic index (BMI) compared with day workers23,24. Several studies displayed a negative relationship between shift work and metabolism. Shift workers exhibited a lowered glucose and lipid tolerance following a change from day to night shift work25,26,27. Insulin resistance was also demonstrated to be more recurrent in shift workers who were 50 years or younger28.

Another study equated the risk of shift work to the risk of smoking one pack of cigarettes a day in spite of controlling for other confounders and risk factors29. The complexity of the phenotypic expression of obesity is influenced by numerous factors such as stress, social rhythm, altered patterns of transcriptional genes, altered glucose and lipid homoeostasis, disruption of the central and peripheral oscillators and a decreased thermogenic response during night eating30.

Emerging evidence also suggests that chrononutrition is influenced by an individual’s “chronotype”.

Chronotype is a behaviour manifestation of an individual’s internal circadian clock system, whereby they can be classified to have a preference for the morning or evening9. Individuals with an “evening chronotype” or also termed “later chronotype” are biologically driven to consume foods later in the day31.

There has been a relatively strong association between breakfast skipping and insulin resistance or type 2 diabetes shown in some studies. In a 16-year follow-up cohort study, using the Cox proportional hazards analysis, it was shown that after adjusting for known risk factors of T2D including BMI, US men who skipped breakfast had a 21% higher risk of developing T2D compared with men who consumed breakfast32. In another randomised crossover trial, 10 women underwent a 2-week intervention with a 2-week washout period of either skipping or consuming breakfast. The study demonstrated that omitting breakfast led to a significantly higher energy intake, fasting total and LDL cholesterol, and a significantly lower postprandial insulin sensitivity33. Individuals who have a preference for late-night dinner consumption (later chronotypes) may have a tendency to skip breakfast the following morning34. This may be due to insufficient time to eat during the day or due to reduced hunger in the morning. A large cross-sectional study in healthy Japanese individuals, after adjusting for body mass index (BMI), showed that breakfast skipping was not the sole cause of hyperglycaemia but also a result of late-night dinner consumption35. Kobayashi et al. reported that healthy males who skipped breakfast and then consumed large meals at lunch and dinner, had greater postprandial glucose, especially after dinner36. An acute study in type 2 diabetics, who were classified as later chronotypes and skipped breakfast, had poorer glycaemic control as indicated by their significantly higher HbA1c values31. A cross-sectional study by Sakai et al. reported that there was an independent association of having a late-night dinner and skipping breakfast with poor glycaemic control in individuals with type 2 diabetes37.

The omission of breakfast further compounded by late-night meal consumption, may delay circadian rhythms. These individuals do not consume breakfast due to lack of appetite signalling brought about by the disruption of biological clocks38. Due to inappropriate time of feeding, the misalignment of the circadian clock leads to worsening of glycaemic control and an increased risk of developing type 2 diabetes.

However, there is another body of evidence suggesting that breakfast is not the most important meal of the day, rather, it is ‘just another meal’ as there has yet to be an established causal relationship between skipping breakfast and its negative metabolic implications. The authors highlighted that in most breakfast studies comparing the effects of consuming or skipping breakfast, the duration of overnight fast was not accounted for39. This was an important confounder that should be considered. For example, two breakfast consumers both had their last meals at 2200 h the night before, one ate breakfast the next morning at 0600 h compared with one that consumed breakfast only at 1000 h, the difference in duration of overnight fast could potentially be the cause for a prominent difference metabolically. Conversely, regardless of time of meal consumed, similar durations of overnight fast may have resulted in similar metabolic profiles.

Likewise, despite routine evidences indicating that skipping breakfast resulted in an increased BMI and an overcompensation of energy consumed later during the day, no causality has been established40,41. Zilberter and Zilberter also discussed indirect potential benefits of omitting breakfast in relation to intermittent fasting where the suppression of appetite could lead to voluntary caloric reduction and caloric restriction may have profound metabolic effects on human health39,42,43.

Meal intakes timing of ingestion: morning versus dinner

Evidence suggests that meal ingestion in the morning and late evening (time of day) influence glucose metabolism in humans. Earlier studies, using mixed meals or glucose infusion, have reported circadian responses of reduced glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity in healthy participants for the evening rather than in the morning44,45,46,47. An acute study by Sato et al. examined the effects of a late evening meal on diurnal variation of blood glucose in healthy individuals, assessed by continuous glucose monitoring (CGMS™)48. There was an increase in blood glucose after the late evening meal which shifted towards later at night, with peaking of blood glucose observed during sleep48. Late evening meals may cause postprandial hyperglycaemia with this decrease in glucose tolerance from morning towards the night.

A cohort study was the first to show the relationship between late-night dinner consumption and glycaemic control in type 2 diabetics, whereby having a late dinner meal after 8 pm was independently associated with an increase in HbA1c37. In some acute trials, both healthy individuals49,50 and type 2 diabetics51 showed significantly higher blood glucose and insulin values after night-time meals. These studies deduce that the disruption of the circadian rhythm led to the exacerbation of the physiological nocturnal decrease of glucose tolerance. Peter et al. showed that type 2 diabetic subjects who ate three identical meals had glucose excursions that were higher in the morning than in the evening52. There was increased glucose tolerance in response to the first and third meals of the day, irrespective of glycaemic control. There was also a change in circadian variation in insulin sensitivity in type 2 diabetics52. Type 2 diabetics exhibit a different daily circadian pattern from healthy individuals, with increased insulin sensitivity towards the night, and higher glucose excursions in the morning than in the evening.

Methods to improve glycaemic control at dinner has been reported by some authors. Dinner that was divided into two smaller meals reduced post-meal glycaemic excursions, due to the “second-meal effect” phenomenon, by enhancing β-cell responsiveness53 at the second dinner meal induced by the first meal49,51. It was also suggested that if meal size and carbohydrate quantities were smaller, postprandial glucose can be ameliorated in both healthy and type 2 diabetics.

In summary, time of day is indicative of having an influence on the postprandial glucose response to a meal. There is a defined circadian pattern for postprandial glycaemia for similar meals consumed either in the evening or morning. These studies illustrate that glucose metabolism is not only affected by what and how much you eat alone, but also when the meal is consumed. However, more data from well-designed epidemiological studies is necessary to prove causality.

Time of nutrient intake and glucose metabolism

It is evident from literature that there is an obvious circadian pattern to have a higher postprandial glucose response to meals at night than in the morning, in healthy individuals. With the increasing trend of people shifting towards a late-eating pattern (later chronotype) due to several lifestyle factors and changes, understanding how diet can be manipulated is crucial to ensure circadian synchronization so as to improve glycaemic control. Meal composition, in addition to meal timing, also appears to influence glucose levels.

Calories

Current evidence suggests that the time of day in which the amount of calories is consumed, can affect glycaemic control. Some animal studies have shown that there is an impairment of peripheral clock gene expressions due to skipping breakfast or reduced food intake in the first meal of the day, along with high-caloric dinners (despite no differences in daily total caloric intake), resulting in higher daily glucose excursions54,55.

A cohort study reported that when most of the day’s calorie requirements were consumed at dinner, there was a 2-fold greater incidence of diabetes in older men and women56. In a randomized, parallel-arm designed study, the effect of consuming a high calorie meal in the morning (i.e. breakfast) versus a high calorie meal in the evening, was assessed in overweight and obese women (with metabolic syndrome)57. The group who consumed more calories at breakfast saw a greater reduction in fasting blood glucose and insulin when compared with consuming more calories at dinner57. This was taking into account the fact that there was a similar daily calorie intake for both arms. Furthermore, a reduction in glycaemic and insulinemic responses for oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) after a high calorie breakfast compared with a high calorie dinner was also observed57. In a crossover study, type 2 diabetic participants who were given a high-caloric breakfast/low caloric dinner (contrasting arm was a low caloric breakfast/high-caloric dinner), was associated with reduction in postprandial hyperglycaemia, increase in insulin and glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) for the whole day58. The results of this study by Jakubowicz et al. demonstrated the diurnal variation of glycaemic control in type 2 diabetics58. The amount of calories consumed at breakfast or dinner seemed to have an influence on the daily rhythm of postprandial glycaemic excursions and insulin levels.

For most people, it would be unrealistic to avoid eating at night. With night-time eating being associated with poor glucose control and the increased risk of type 2 diabetes, manipulating meal composition of late meals or reducing the portion size may be crucial strategies to positively impact on postprandial glucose.

Carbohydrates

The quantity, quality type, and rate of digestion of dietary carbohydrates are the primary determinants of postprandial glucose levels and insulin response59,60. Therefore, they all play an important role in the diet we consume, when it comes to circadian rhythmicity and glycaemic control. Epidemiological studies have shown that the time of consumption of carbohydrate-rich meals, if at the start of the day, has protective benefits against the development of diabetes61,62. Acute trials have reported that, specifically nocturnal consumption of carbohydrates, an increased absorption of dietary cabohydrates resulted in a higher postprandial glucose profile the following morning63,64.

Glycemic index (GI) and meal timings

The glycemic index (GI) is defined as the blood glucose raising potential of carbohydrate foods65. Low GI carbohydrates have shown to be beneficial as they have a lower impact on blood glucose concentrations and protect against hypoglycaemia66. There is good evidence to suggest that it also avoids large fluctuations in blood glucose levels67.

Some intervention studies have aimed to establish if varying the GI and the time at which meals are consumed impacts on postprandial glucose and insulin responses. A four-way, randomized crossover study in healthy individuals, by Morgan et al. compared the glycaemic effects of varying the GI and glycaemic load (GL) (GL = GI × carbohydrate content) and the timing of meal consumption, with most of the energy consumed either for breakfast or for dinner68. In their first observation, higher GL meals consumed in the evening led to higher glucose and insulin response compared with consuming the same meal in the morning. In the second part of the study, a high GI diet given in the evening, produced an even more pronounced effect on glucose and insulin68. These results confirmed that the quality and quantity of carbohydrates, i.e. the GI and GL in addition to the time at which the meal is consumed, influences glycaemic control and insulin secretion. An additional randomised crossover study in healthy subjects investigated the effect of low and high GI meals on glucose levels, when given in the earlier or latter part of the day69. Postprandial glucose response in the evening was greater even after the low GI meal69. These results suggest that low GI foods, even if they were consumed in the night, was less efficient in glucose control. Low GI foods were more effective in glucose control in the morning. This could possibly be explained by the changes in insulin sensitivity which has been reported to decrease during the day70. Furthermore, an additional influence is due to hormones such as glucagon and cortisol which are affected by circadian rhythms71, and in turn influence insulin secretion and glycaemic response. A recent intervention investigated the timing of low GI meals in the morning (0800 h), evening (2000h) and midnight (0000 h)72. The low GI meals consumed in the evening and midnight resulted in higher glucose excursions with concomitant higher insulin levels, compared with the morning72. Collectively, these studies have shown that having a low GI meal, irrespective of meal size, improved glycaemic response in the morning but had little impact at night. This temporal difference has been associated with the effect that the endogenous circadian rhythm has on glucose metabolism73.

Fats

Epidemiological studies has reported that consumption of more carbohydrates than fats in the morning prevents the development of diabetes and metabolic syndrome61,62. The effect of manipulating fats, as well as carbohydrates, in day and night meals on postprandial glycaemic response has been undertaken in a few experimental studies. A randomized crossover trial in healthy men compared whether consuming a high carbohydrate diet or a high fat diet during different timings in a 24 h period, would produce different plasma glucose responses74. A more rapid rise in plasma glucose was observed with the high carbohydrate diet compared with the high fat diet. There was also a circadian pattern in plasma glucose concentration, with the circadian effect coming from the high fat diet consumption74. A recent randomised crossover trial comparing two isocaloric meals, differing in total sugar and saturated fat, was undertaken during a simulated night shift work in overweight males with high fasting lipids75. Although this study resulted in no significant changes in circadian gene expressions, modifying a meal by reducing saturated fat and sugar for a dinner meal was associated with improved glucose response75. Whilst the quality of fat ingested is known to influence metabolism, there is a lack of consistent information on the degree of saturation and chain length of fatty acids influencing postprandial glycaemia and lipidemia. This further highlights the need to investigate the chronobiology of dietary fat intake on glucose homoeostasis.

Proteins

A recent crossover study on healthy participants examined if a high protein meal could attenuate postprandial glucose in the morning and at night76. The effect of a high protein meal showed a significant modulation of the glucose response at night, with a significantly lower incremental area under the curve (iAUC) compared with a standard meal76. There were no differences in iAUC glucose for morning between the high protein test meal and standard meals. In addition, there were no differences noted for insulin responses between meal type in the morning or night76. These findings suggest that increasing the amount of proteins in a meal can reduce postprandial glucose at night. This can be beneficial for people who are late chronotypes or late-night eaters, who are more predisposed to glycaemic excursions and therefore reduce the risk of hyperglycaemia. The glucose-attenuation property of dietary protein seems to be also influenced by the timing of consumption. However, there are limited studies to support this and more needs to be done on the glycaemic and insulinemic impact of protein in meals, in accordance to timing of day.

Timing fat and protein foods to lower glycaemic response of carbohydrate meals

The consumption of high GI starchy foods, such as white rice and white bread, have been implicated in the development of type 2 diabetes. Therefore, investigating the timing of fat and protein (including amino acids) co-ingestion with carbohydrate foods remains a novel food-based intervention to reduce glycaemic response (GR).

The ingestion of fat in the form of olive oil, half an hour before a potato meal, was found to attenuate postprandial glucose and insulin in type 2 diabetics77. Milk protein given as a preload prior to consuming bread rather than coingesting both foods, was found to significantly lower postprandial glycaemia and insulinemia78. Essence of chicken (EOC), a chicken meat extract which is a rich source of peptides and amino acids, is commonly consumed in Asian countries. There has been a long debate on the timing at which EOC should be consumed for maximum health benefits. One study showed that the co-ingestion of EOC with white bread was a simple strategy to reduce the glycaemic response of bread79. More interestingly, the same group found that the ingestion of EOC 15 min prior to the consumption of white rice elicited the greatest reduction in glycaemia80. The results suggest that timing of ingestion plays a significant role in insulin secretion which in turn impacts on glucose homoeostasis. A most recent study by the team also examined meal sequence as being an important regulator of postprandial glucose. Consumption of vegetables, followed by meat and then lastly rice, was the best sequence to attenuate glycaemic response without an increased demand for insulin in healthy adults81. The sequence of presenting food and their timing of consumption has a great impact in modulating glycaemic response.

In summary, it is now recognized that there is an increased glycaemic excursion and reduced insulin sensitivity when meals are consumed at night than during the day. These studies highlight the interaction of meal timing and nutrient composition (carbohydrate, fat and protein) on glucose metabolism. The application of these observations also include the timing at which fat and protein foods are consumed during a carbohydrate-rich meal. A more recent observation is how the sequence of food presentation within a meal can also influence glycaemic and insulinemic response. Collectively, these observations are easily transferable as public health advocacy to communities that have a high prevalence of type 2 diabetes (pre-diabetes) and are dependent on a high carbohydrate diet.

Timing the consumption of food components for glycaemic control

Some food components have been identified as having the ability to modulate circadian clocks and impact glycaemic control, with many such studies being conducted in animals14. A few human studies have reported the role of food components when consumed at specific timings. Green tea polyphenols, such as catechins, have shown to be beneficial in decreasing fasting and postprandial glucose82,83. Most recently, it was demonstrated for the first time that ingesting catechin-rich green tea in the evening was able to reduce postprandial plasma glucose concentrations compared with the placebo tea given at the same time84. Epidemiological studies have reported the protective effect of coffee consumption on the development of diabetes85,86. The effects of coffee on postprandial glucose differs when consumed at different times of the day, indicating that timing of coffee intake may have a preventative effect on type 2 diabetes risk. A prospective cohort study reported an association between both caffeinated coffee and decaffeinated coffee and reduced risk of type 2 diabetes, but only when coffee was consumed at lunch time87. In a randomized crossover trial, caffeinated coffee consumed in the morning had a higher postprandial glucose and insulin response to a later meal88. These small but important findings suggest that the circadian clocks can be affected by food components, depending on the time they are consumed. This is an approach for maintaining glucose homoeostasis that merits further investigation.

Conclusion

Whilst chrononutrition is an advancing science, there still remains much to be learnt about the nature and timing of diet provision in regulating glucose homoeostasis. This review has demonstrated that the choice of food alone does not dictate glycaemic response. The emerging field of chrononutrition indicates that the timing and order of food presentation within and between meals could also significantly influence postprandial glycaemia. There still remains much to be learnt. We hope that this paper will stimulate further research that will enable us to translate how chronobiology may be effectively used in communities around the world that are confronted with the burgeoning prevalence of type 2 diabetes.

Key messages

An overall summary of key studies reporting the effects of meal timings and dietary factors on glycaemic control is shown in Table 1.

-

Meal timing has a major effect on type 2 diabetes. It is therefore important to consider the timing of meal consumption rather than focus on the nutritional value of a meal alone.

-

Eating a carbohydrate-rich meal at night results in increased postprandial glycaemia compared with an identical meal in the morning. Therefore, modifying the macronutrient composition of meals, by increasing protein and fat content, can be a simple strategy to improve glycaemia for meals consumed at that night.

-

The benefits of consuming meals early in the day should be encouraged in diabetics.

-

Eating low GI foods in the morning improves glycaemic response to a greater effect than at night.

-

Timing of fat and protein (including amino acids) consumption with carbohydrate foods, such as bread and rice, can reduce the glycaemic response.

-

The order of food presentation considerably influences the glycaemic response. For a rice-based meal, following the sequence of consuming vegetables first, followed by meat and then lastly rice, has great potential of reducing the postprandial blood glucose.

References

Zheng, Y., Ley, S. H. & Hu, F. B. Global aetiology and epidemiology of type 2 diabetes mellitus and its complications. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 14, 88 (2017).

Herman, W. H. in Diabetes Mellitus in Developing Countries and Underserved Communities (ed. Dagogo-Jack, S.) 1–5 (Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2017).

Kurose, T., Hyo, T., Yabe, D. & Seino, Y. The role of chronobiology and circadian rhythms in type 2 diabetes mellitus: implications for management of diabetes. Chronophysiology Ther. 4, 41–49 (2014).

Albrecht, U. & Eichele, G. The mammalian circadian clock. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 13, 271–277 (2003).

Huang, W., Ramsey, K. M., Marcheva, B. & Bass, J. Circadian rhythms, sleep, and metabolism. J. Clin. Investig. 121, 2133–2141 (2011).

Ibata, Y. et al. Functional morphology of the suprachiasmatic nucleus. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 20, 241–268 (1999).

Johnston, J. D. Physiological responses to food intake throughout the day. Nutr. Res. Rev. 27, 107–118 (2014).

Oike, H., Oishi, K. & Kobori, M. Nutrients, clock genes, and chrononutrition. Curr. Nutr. Rep. 3, 204–212 (2014).

Almoosawi, S. et al. Chronotype: implications for epidemiologic studies on chrono-nutrition and cardiometabolic health. Adv. Nutr. 10, 30–42 (2018).

Wong, P. M., Hasler, B. P., Kamarck, T. W., Muldoon, M. F. & Manuck, S. B. Social jetlag, chronotype, and cardiometabolic risk. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 100, 4612–4620 (2015).

Scheer, F. A., Hilton, M. F., Mantzoros, C. S. & Shea, S. A. Adverse metabolic and cardiovascular consequences of circadian misalignment. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 4453–4458 (2009).

Qian, J. & Scheer, F. A. Circadian system and glucose metabolism: implications for physiology and disease. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 27, 282–293 (2016).

Kalsbeek, A., la Fleur, S. & Fliers, E. Circadian control of glucose metabolism. Mol. Metab. 3, 372–383 (2014).

Froy, O. The relationship between nutrition and circadian rhythms in mammals. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 28, 61–71 (2007).

Czeisler, C. A. & Klerman, E. B. Circadian and sleep-dependent regulation of hormone release in humans. Recent Prog. Horm. Res. 54, 97–130 (1999).

Marcheva, B. et al. Disruption of the clock components CLOCK and BMAL1 leads to hypoinsulinaemia and diabetes. Nature 466, 627 (2010).

Gale, J. E. et al. Disruption of circadian rhythms accelerates development of diabetes through pancreatic beta-cell loss and dysfunction. J. Biol. Rhythms 26, 423–433 (2011).

Shi, S.-Q., Ansari, T. S., McGuinness, O. P., Wasserman, D. H. & Johnson, C. H. Circadian disruption leads to insulin resistance and obesity. Curr. Biol. 23, 372–381 (2013).

Bandin, C. et al. Meal timing affects glucose tolerance, substrate oxidation and circadian-related variables: a randomized, crossover trial. Int. J. Obes. 39, 828 (2015).

Wehrens, S. M. T. et al. Meal timing regulates the human circadian system. Curr. Biol. 27, 1768–75.e3 (2017).

Gill, S. & Panda, S. A smartphone app reveals erratic diurnal eating patterns in humans that can be modulated for health benefits. Cell Metab. 22, 789–798 (2015).

Antunes, L., Levandovski, R., Dantas, G., Caumo, W. & Hidalgo, M. Obesity and shift work: chronobiological aspects. Nutr. Res. Rev. 23, 155–168 (2010).

Morikawa, Y. et al. Effect of shift work on body mass index and metabolic parameters. Scand. J. Work, Environ. Health 33, 45–50 (2007).

Zimberg, I. Z., Fernandes Junior, S. A., Crispim, C. A., Tufik, S. & de Mello, M. T. Metabolic impact of shift work. Work 41(Suppl 1), 4376–4383 (2012).

Ribeiro, D., Hampton, S. & Morgan, L. Altered postprandial hormone and metabolic responses in a simulated shift work environment. Occup. Health Ind. Med. 1, 40–41 (1999).

Lund, J., Arendt, J., Hampton, S., English, J. & Morgan, L. Postprandial hormone and metabolic responses amongst shift workers in Antarctica. J. Endocrinol. 171, 557–564 (2001).

Hampton, S. et al. Postprandial hormone and metabolic responses in simulated shift work. J. Endocrinol. 151, 259–267 (1996).

Nagaya, T., Yoshida, H., Takahashi, H. & Kawai, M. Markers of insulin resistance in day and shift workers aged 30–59 years. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 75, 562–568 (2002).

Whitehead, D. C., Thomas, H. Jr. & Slapper, D. R. A rational approach to shift work in emergency medicine. Ann. Emerg. Med. 21, 1250–1258 (1992).

Knutsson, A. Health disorders of shift workers. Occup. Med. 53, 103–108 (2003).

Reutrakul, S. et al. The relationship between breakfast skipping, chronotype, and glycemic control in type 2 diabetes. Chronobiol. Int. 31, 64–71 (2014).

Mekary, R. A., Giovannucci, E., Willett, W. C., van Dam, R. M. & Hu, F. B. Eating patterns and type 2 diabetes risk in men: breakfast omission, eating frequency, and snacking. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 95, 1182–1189 (2012).

Farshchi, H. R., Taylor, M. A. & Macdonald, I. A. Deleterious effects of omitting breakfast on insulin sensitivity and fasting lipid profiles in healthy lean women. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 81, 388–396 (2005).

Meule, A., Roeser, K., Randler, C. & Kübler, A. Skipping breakfast: morningness-eveningness preference is differentially related to state and trait food cravings. Eat. Weight Disord.-Stud. Anorex., Bulim. Obes. 17, e304–e308 (2012).

Nakajima, K. & Suwa, K. Association of hyperglycemia in a general Japanese population with late-night-dinner eating alone, but not breakfast skipping alone. J. Diabetes Metab. Disord. 14, 16 (2015).

Kobayashi, F. et al. Effect of breakfast skipping on diurnal variation of energy metabolism and blood glucose. Obes. Res. Clin. Pract. 8, e249–e57 (2014).

Sakai, R. et al. Late-night-dinner is associated with poor glycemic control in people with type 2 diabetes: The KAMOGAWA-DM cohort study. Endocr. J. 65, 395–402 (2018).

Silva, C. M. et al. Chronotype, social jetlag and sleep debt are associated with dietary intake among Brazilian undergraduate students. Chronobiol. Int. 33, 740–748 (2016).

Zilberter, T. & Zilberter, E. Y. Breakfast: to skip or not to skip? Front Public Health 2, 59 (2014).

Van Lippevelde, W. et al. Associations between family-related factors, breakfast consumption and BMI among 10-to 12-year-old European children: the cross-sectional ENERGY-study. PLoS ONE 8, e79550 (2013).

Timlin, M. T., Pereira, M. A., Story, M. & Neumark-Sztainer, D. Breakfast eating and weight change in a 5-year prospective analysis of adolescents: project EAT (eating among teens). Pediatrics 121, e638–e645 (2008).

Willcox, B. J. et al. Caloric restriction, caloric restriction mimetics, and healthy aging in Okinawa. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1114, 434–455 (2007).

Dutton, S. B. et al. Protective effect of the ketogenic diet in Scn1a mutant mice. Epilepsia 52, 2050–2056 (2011).

Malherbe, C., de Gasparo, M., de Hertogh, R. & Hoem, J. J. Circadian variations of blood sugar and plasma insulin levels in man. Diabetologia 5, 397–404 (1969).

Service, F. J. et al. Effects of size, time of day and sequence of meal ingestion on carbohydrate tolerance in normal subjects. Diabetologia 25, 316–321 (1983).

Van Cauter, E., Shapiro, E. T., Tillil, H. & Polonsky, K. S. Circadian modulation of glucose and insulin responses to meals: relationship to cortisol rhythm. Am. J. Physiol.-Endocrinol. Metab. 262, E467–E475 (1992).

Cauter, E. V., Desir, D., Decoster, C., Fery, F. & Balasse, E. O. Nocturnal decrease in glucose tolerance during constant glucose infusion. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 69, 604–611 (1989).

Sato, M. et al. Acute effect of late evening meal on diurnal variation of blood glucose and energy metabolism. Obes. Res. Clin. Pract. 5, e220–e8. (2011).

Kajiyama, S. et al. Divided consumption of late-night-dinner improves glucose excursions in young healthy women: a randomized cross-over clinical trial. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 136, 78–84 (2018).

Al-Naimi, S., Hampton, S. M., Richard, P., Tzung, C. & Morgan, L. M. Postprandial metabolic profiles following meals and snacks eaten during simulated night and day shift work. Chronobiol. Int. 21, 937–947 (2004).

Imai, S. et al. Divided consumption of late-night-dinner improves glycemic excursions in patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomized cross-over clinical trial. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 129, 206–212 (2017).

Peter, R. et al. Daytime variability of postprandial glucose tolerance and pancreatic B‐cell function using 12‐h profiles in persons with type 2 diabetes. Diabet. Med. 27, 266–273 (2010).

Jakubowicz, D. et al. Fasting until noon triggers increased postprandial hyperglycemia and impaired insulin response after lunch and dinner in individuals with type 2 diabetes: a randomized clinical trial. Diabetes Care. 38, 1820–1826 (2015).

Fuse, Y. et al. Differential roles of breakfast only (one meal per day) and a bigger breakfast with a small dinner (two meals per day) in mice fed a high-fat diet with regard to induced obesity and lipid metabolism. J. Circadian Rhythms 10, 4 (2012).

Wu, T. et al. Differential roles of breakfast and supper in rats of a daily three-meal schedule upon circadian regulation and physiology. Chronobiol. Int. 28, 890–903 (2011).

Bo, S. et al. Consuming more of daily caloric intake at dinner predisposes to obesity. A 6-year population-based prospective cohort study. PLoS ONE 9, e108467 (2014).

Jakubowicz, D., Barnea, M., Wainstein, J. & Froy, O. High Caloric intake at breakfast vs. dinner differentially influences weight loss of overweight and obese women. Obesity 21, 2504–2512 (2013).

Jakubowicz, D. et al. High-energy breakfast with low-energy dinner decreases overall daily hyperglycaemia in type 2 diabetic patients: a randomised clinical trial. Diabetologia 58, 912–919 (2015).

Thomas, T. & Pfeiffer, A. F. H. Foods for the prevention of diabetes: how do they work? Diabetes/Metab. Res. Rev. 28, 25–49 (2012).

Wolever, T. M. S. Dietary carbohydrates and insulin action in humans. Br. J. Nutr. 83(S1), S97–S102 (2007).

Almoosawi, S., Prynne, C., Hardy, R. & Stephen, A. Time-of-day and nutrient composition of eating occasions: prospective association with the metabolic syndrome in the 1946 British birth cohort. Int. J. Obes. 37, 725 (2013).

Almoosawi, S., Prynne, C., Hardy, R. & Stephen, A. Diurnal eating rhythms: association with long-term development of diabetes in the 1946 British birth cohort. Nutr., Metab. Cardiovascular Dis. 23, 1025–1030 (2013).

Kessler, K. et al. The effect of diurnal distribution of carbohydrates and fat on glycaemic control in humans: a randomized controlled trial. Sci. Rep. 7, 44170 (2017).

Tsuchida, Y., Hata, S. & Sone, Y. Effects of a late supper on digestion and the absorption of dietary carbohydrates in the following morning. J. Physiological Anthropol. 32, 9 (2013).

Jenkins, D. J. et al. Glycemic index of foods: a physiological basis for carbohydrate exchange. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 34, 362–366 (1981).

Ludwig, D. S. The glycemic index: physiological mechanisms relating to obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. JAMA 287, 2414–2423 (2002).

Kaur, B., Ranawana, V., Teh, A.-L. & Henry, C. J. K. The impact of a low glycemic index (GI) breakfast and snack on daily blood glucose profiles and food intake in young Chinese adult males. J. Clin. Transl. Endocrinol. 2, 92–98 (2015).

Morgan, L. M., Shi, J.-W., Hampton, S. M. & Frost, G. Effect of meal timing and glycaemic index on glucose control and insulin secretion in healthy volunteers. Br. J. Nutr. 108, 1286–1291 (2012).

Gibbs, M., Harrington, D., Starkey, S., Williams, P. & Hampton, S. Diurnal postprandial responses to low and high glycaemic index mixed meals. Clin. Nutr. 33, 889–894 (2014).

Carrasco-Benso, M. P. et al. Human adipose tissue expresses intrinsic circadian rhythm in insulin sensitivity. FASEB J. 30, 3117–3123 (2016).

Gamble, K. L., Berry, R., Frank, S. J. & Young, M. E. Circadian clock control of endocrine factors. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 10, 466–475 (2014).

Leung, G. K. W., Huggins, C. E. & Bonham, M. P. Effect of meal timing on postprandial glucose responses to a low glycemic index meal: a crossover trial in healthy volunteers. Clin. Nutr. 38, 465–471 (2019).

Morris, C. J. et al. Endogenous circadian system and circadian misalignment impact glucose tolerance via separate mechanisms in humans. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci USA. 112, E2225–E2234 (2015).

Holmbäck, U. et al. Metabolic responses to nocturnal eating in men are affected by sources of dietary energy. J. Nutr. 132, 1892–1899 (2002).

Bonham, M. P. et al. Effects of macronutrient manipulation on postprandial metabolic responses in overweight males with high fasting lipids during simulated shift work: a randomized crossover trial. Clin. Nutr. 39, 369–377 (2019).

Davis, R., Bonham, M. P., Nguo, K. & Huggins, C. E. Glycaemic response at night is improved after eating a high protein meal compared with a standard meal: a cross-over study. Clin. Nutr. (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2019.06.014 (in press).

Gentilcore, D. et al. Effects of fat on gastric emptying of and the glycemic, insulin, and incretin responses to a carbohydrate meal in type 2 diabetes. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 91, 2062–2067 (2006).

Sun, L., Tan, K. W. J., Han, C. M. S., Leow, M. K.-S. & Henry, C. J. Impact of preloading either dairy or soy milk on postprandial glycemia, insulinemia and gastric emptying in healthy adults. Eur. J. Nutr. 56, 77–87 (2017).

Sun, L., Wei Jie Tan, K. & Jeyakumar Henry, C. Co-ingestion of essence of chicken to moderate glycaemic response of bread. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 66, 931–935 (2015).

Soong, Y. Y., Lim, J., Sun, L. & Henry, C. J. Effect of co-ingestion of amino acids with rice on glycaemic and insulinaemic response. Br. J. Nutr. 114, 1845–1851 (2015).

Sun, L., Goh, H. J., Govindharajulu, P., Leow, M. K.-S. & Henry, C. J. Postprandial glucose, insulin and incretin responses differ by test meal macronutrient ingestion sequence (PATTERN study). Clin. Nutr. (2019). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2019.04.001 (in press).

Zheng, X.-X. et al. Effects of green tea catechins with or without caffeine on glycemic control in adults: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 97, 750–762 (2013).

Venables, M. C., Hulston, C. J., Cox, H. R. & Jeukendrup, A. E. Green tea extract ingestion, fat oxidation, and glucose tolerance in healthy humans. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 87, 778–784 (2008).

Takahashi, M. et al. Effects of timing of acute catechin-rich green tea ingestion on postprandial glucose metabolism in healthy men. J. Nutritional Biochem. 73, 108221 (2019).

Van Dam, R. M. & Feskens, E. J. Coffee consumption and risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Lancet 360, 1477–1478 (2002).

Van Dam, R. M. & Hu, F. B. Coffee consumption and risk of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review. JAMA 294, 97–104 (2005).

Sartorelli, D. S. et al. Differential effects of coffee on the risk of type 2 diabetes according to meal consumption in a French cohort of women: the E3N/EPIC cohort study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 91, 1002–1012 (2010).

Moisey, L. L., Robinson, L. E. & Graham, T. E. Consumption of caffeinated coffee and a high carbohydrate meal affects postprandial metabolism of a subsequent oral glucose tolerance test in young, healthy males. Br. J. Nutr. 103, 833–841 (2010).

Bo, S. et al. Is the timing of caloric intake associated with variation in diet-induced thermogenesis and in the metabolic pattern? A randomized cross-over study. Int. J. Obes. 39, 1689 (2015).

Takahashi, M. et al. Effects of meal timing on postprandial glucose metabolism and blood metabolites in healthy adults. Nutrients 10, 1763 (2018).

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Henry, C.J., Kaur, B. & Quek, R.Y.C. Chrononutrition in the management of diabetes. Nutr. Diabetes 10, 6 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41387-020-0109-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41387-020-0109-6

Comments

Post a Comment